This year, we have been working on a visual investigation into Iron March, a neo-Nazi and white supremacist online message board subject to an SQL database leak in November 2019. The leaked data contains the entirety of the site’s information including user names, registered emails, IP addresses of users, all of the forum’s public posts and even private messages between members. We have been using the data in the leak to examine various themes through two iterations of the project.

The first iteration questioned perceptions of what constitutes free speech and highlighted the prevalence of extreme and often violent views occupying the space just below the surface. The second analyses the physical and virtual sites of violence connected to Iron March as well as the ways members are drawn into, and engage with, these spaces.

Throughout our residency we have been engaing with different questions surrounding the recruiting process of far-right platforms. How are people drawn into these spaces? What makes them susceptible to radicalisation? And how does the online landscape perpetuate these cycles of hate?

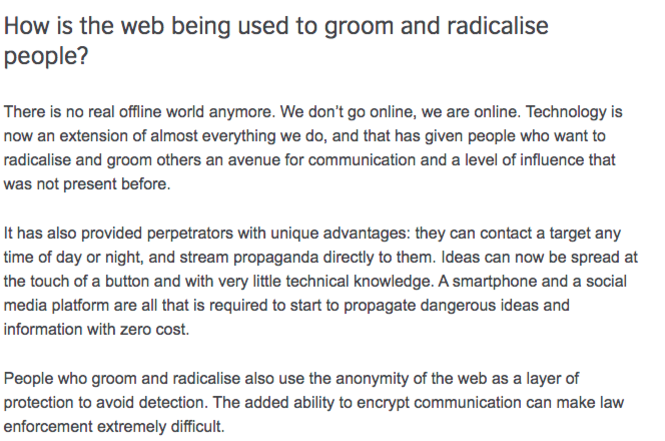

There’s no singular pathway to radicalisation - the far-right use a combination of tactics to recruit their members. Online forums and social media pages are breeding grounds for recruiters, where they seek vulnerable, confused and predominantly young white men to radicalise. Teenagers who feel out of place, frustrated and misunderstood are vulnerable to the idea that someone else is responsible for their discontent. It’s not necessarily the ideology behind white nationalism, anti-feminism or the alt-right that initially appeals to young white men. Participating in the alt-right community online offers the seductive feeling of being part of a brotherhood.

In these groups, they find a home for their rage. An online world filled with people who understand them, who validate their fears and share their insecurities. White supremacists create friendships and build trust through autism chat rooms, youtube channels and gaming forums, promising an ideological paradise. Targeted adverts and comments lead to threads full of racism and conspiracy theories; prompting further searches that present white nationalist outlets, where hate and harassment are normalised.

When governments try to regulate hate speech, they are met with loud opposition from the far-right, under the guise of protecting free speech. Communication is pushed underground, to alternative social networks, whose function in these circumstances is not to secure the freedom of speech for all, but to secure the power for perpetrators to speak without repercussion. To counteract the pull of the far right, young people need a better definition of strength. True strength resides in respecting and lifting up others; not, seeking to dominate them.

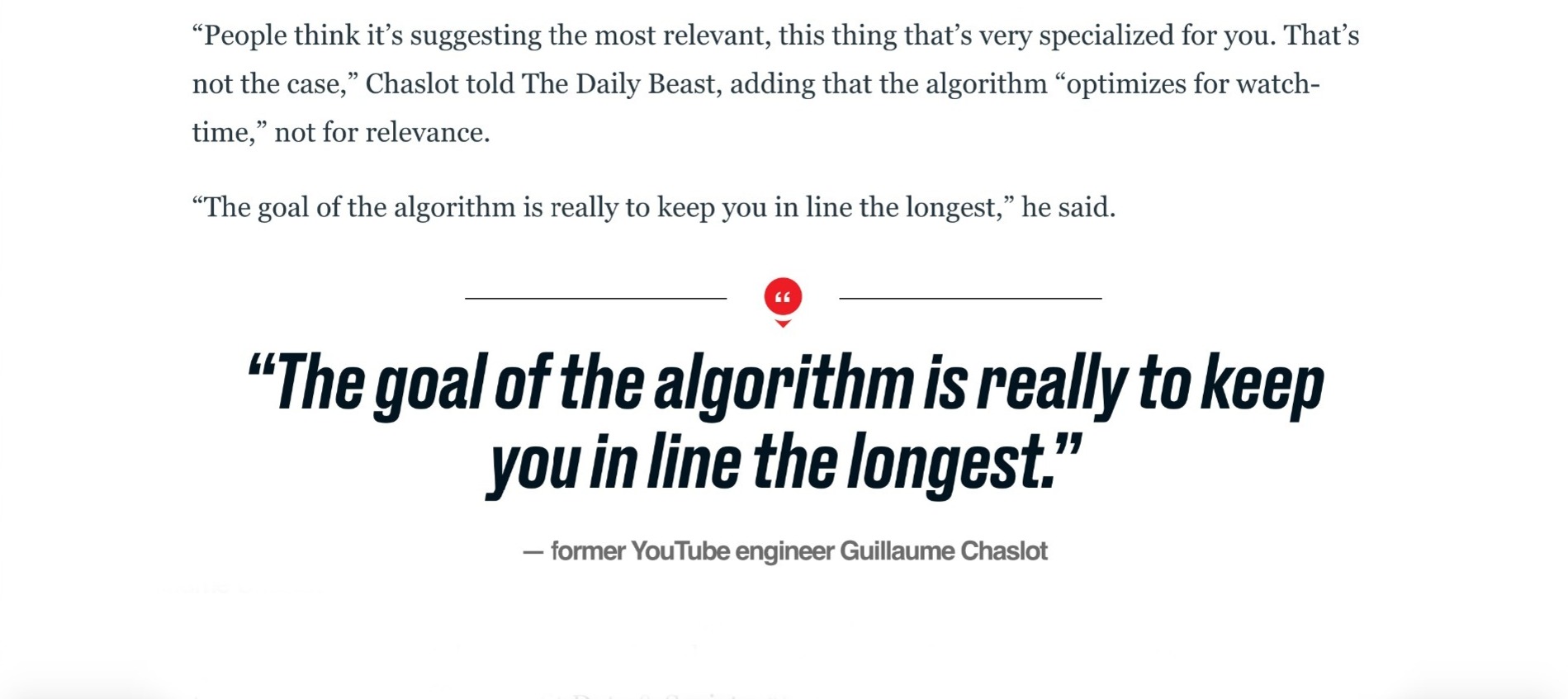

YouTube has been able to fly under the radar because until recently, no one thought of it as a place where radicalization is happening. But it’s where young people are getting their information and entertainment, and it’s a space where creators are broadcasting political content that, at times, is overtly white supremacist.” Becca Lewis, Data & Society.

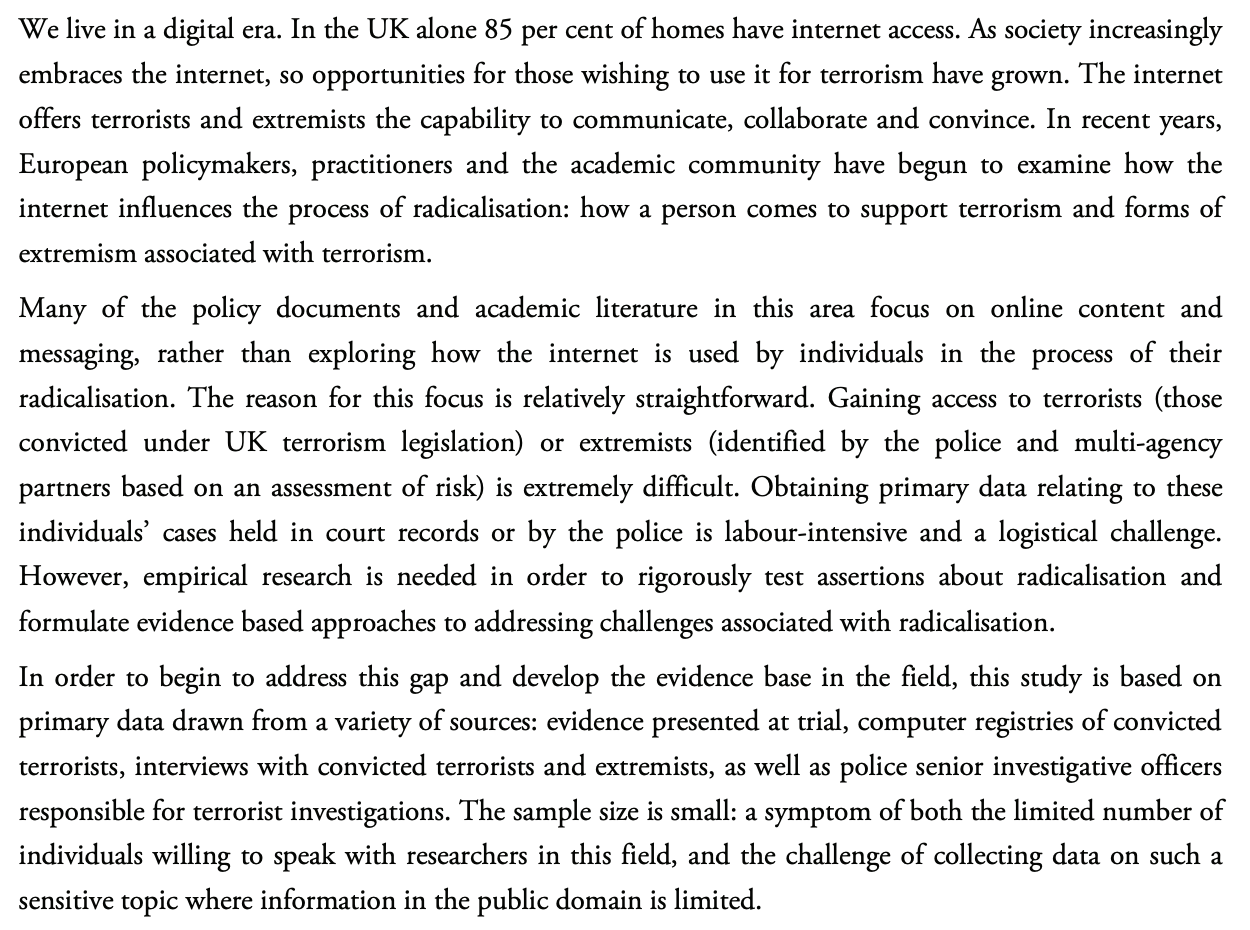

Outdated arguments concerning the relationship between first-person shooter video games and real-life violence continue to surface periodically, alleging virtual desensitisation while obscuring more insidious links between the two. It’s not simulated guns and pixelated gore that lead to extremism; violence and gaming cultures are deeply connected regarding growing far-right ideologies, misogyny and racism.

Players become ‘heroes’ from their bedrooms, often pit against a constructed ‘other’; an enemy reflective of the current affairs of the time. In the 2000s, American video games endorsed aggressive foreign policy and anti-Islamic sentiments; since Brexit, games in the UK have advocated ‘nostalgia for empire’ and frequently reproduced border control scenarios. Video game narratives overrepresent right-wing ideologies in the themes explored and presented within them, virtual actions become instinctual, blurring the line between the player and the characters.

Their experiences within these virtual worlds are made personal, compelling them to accept the character’s ideologies as their own. While simultaneously, technology and the digital increasingly integrate into everyday reality, the divide between real and virtual experience shifts to the divide between independent and conditioned thought.

Occupying the same intangible online space utilised by far-right groups to communicate, recruit and spread hate, we have explored the rapid pace with which a young person could be radicalised without even realising what is happening.

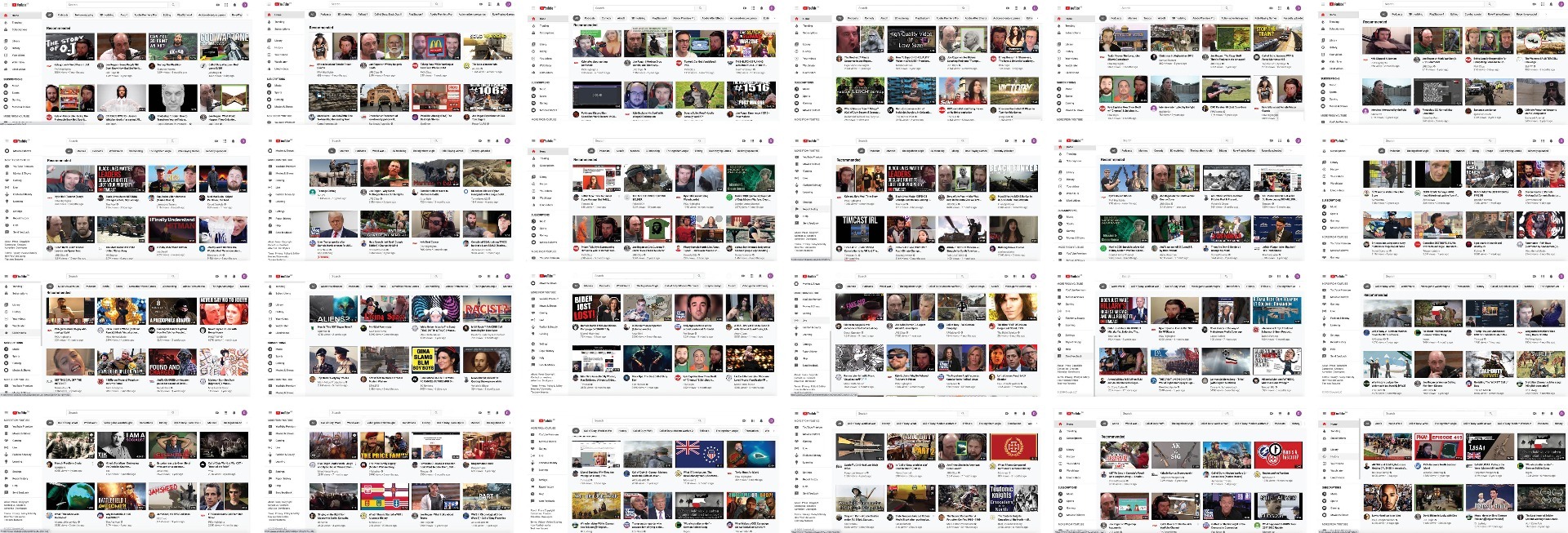

At the beginning of August, we created a fictional teenage character and set up their first YouTube account. The only search term made by this account was “Call of Duty: Modern Warfare”. Following this, our character’s account was left on autoplay for a few hours a day.

Within the first week, mainstream videos of recorded gameplay had been replaced with US marines showing their weapons to shaky handheld cameras and British soldiers eating lunch in their Basra-based camp canteens. By the second, favourable coverage of Trump rallies and far-right activists' opinion pieces filled the homepage. In the third week, the suggested clips had morphed into Tommy Robinson ‘vlogs’, discussions around ‘slapping women’ and detailed reviews of the German weapons used in the Second World War. The fourth week then promoted early 1930s videos of Hitler speeches and songs sung by the Wehrmacht translated into English.

By using simultaneous pixelation and revelation of different elements throughout the research period, the (in)visibility of increasingly far-right ideologies in modern society is challenged without visual reproduction. This character’s journey led our research, while confronting the ease with which they were pulled into more and more extreme spaces. The well-trodden narrative that it is solely the algorithms behind YouTube suggestions that lead users to increasingly extreme videos occupies the same space as the belief that it is only the mock violence of video games that is the problem. In both cases however, it is the myriad of right-leaning content creeping and proliferating into the mainstream unchecked that drives seemingly neutral platforms to increasingly extreme destinations.

The games themselves, and their surrounding platforms, become echo-chambers, perpetuating the constructed ideologies they were made to imitate. It is in these spaces, where predominantly young white men have already been provided with the ‘fuel’ to make them susceptible to radicalisation, that white supremacist recruiters are able to take aim.

If you want to explore the Iron March leak for yourself, here is a useful searchable database of the leaks created by

The Jewish Worker and The Self Agency. The full dataset is also available to download from their site: