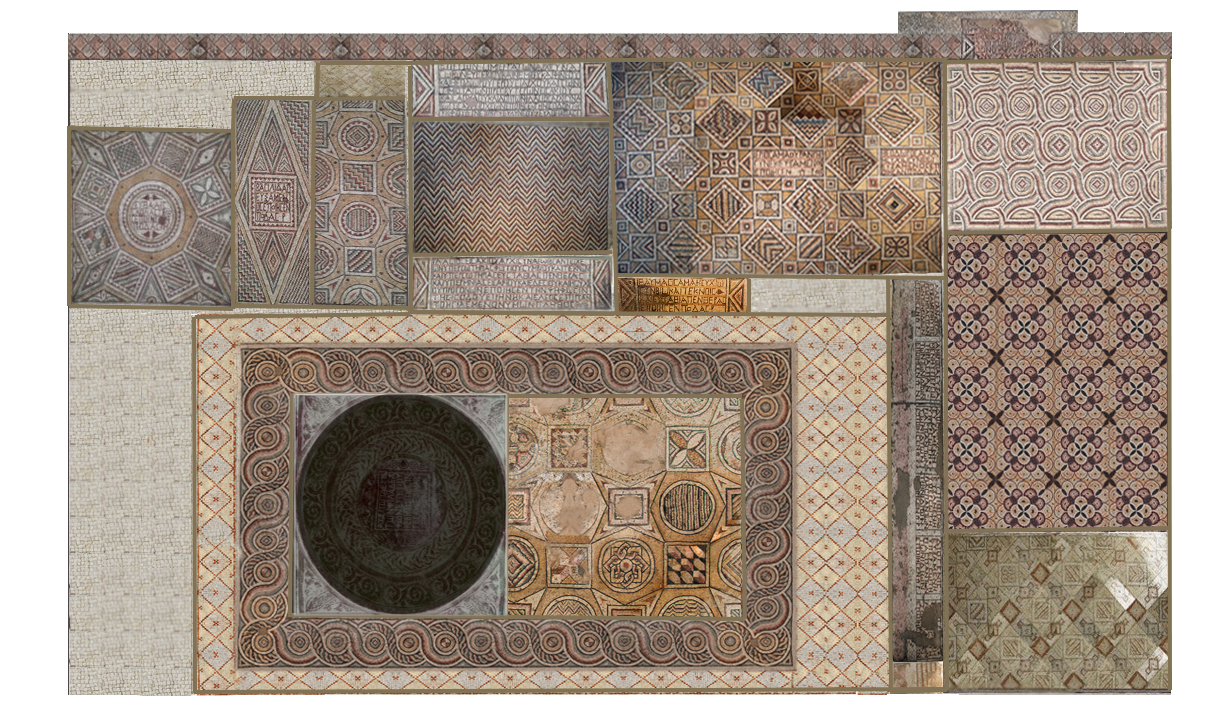

Digital Apamea is both an actual and virtual exhibition in which digital technology is employed to reconstruct the ancient 4th Century synagogue mosaic floor at Apamea on Orontes in Syria.

The synagogue was built in 392 CE (AD). Shortly thereafter it was intentionally destroyed at a time when Roman tolerance yielded to Byzantine intolerance and anti-Semitism per the edicts issued by the emperor Theodosius the Second. Two subsequent basilicae were built over the site of the synagogue. These churches incorporated the former synagogue foundations into the latter structures; the synagogue’s mosaic floor (with Greek donor inscriptions) being buried intact in an act of Damnatio Memoriae. Apamea’s synagogue remained unknown to the world until 1934. Thereafter the mosaics were detached from context and divided between various stakeholders. The excavation reports were destroyed in a fire in Brussels in the late 1940’s. Yet today we can recreate the floor on account of digital technology.

Digital Apamea tells the story of multi-culturalism in Roman Syria, hatred under Byzantine rule, contested space, the archaeology and architecture of Late Antique synagogues and churches, the history of mosaic execution, digital technology and its use for archaeologists (notably as tool to monitor and capture images of illegal excavation at site).

Digital Apamea also explores two artistic legacies: the on-going tradition of Romano-Byzantine mosaic design in Ravenna and also an initiative by the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem in Madaba, Jordan. In the revered city of Madaba, the Patriarchate together with CARITAS runs the “Living Mosaic Project” to train Iraqi refugees from Mosul as mosaicists.

Digital Apamea shares a virtual gallery with visitors and allows the participants to experience what would otherwise be the physical exhibition. It also includes video, presentation and Virtual Reality (VR) experience for all ages.

Digital Apamea©2018 Finalist: International Symposium on Cultural Heritage Conservation and Digitalization, Tsinghua University, Beijing 2018

For further enquiries please contact info@digitalapamea.org or adam.blitz@ronininstitute.org

https//.digitalapamea.org

Beginnings

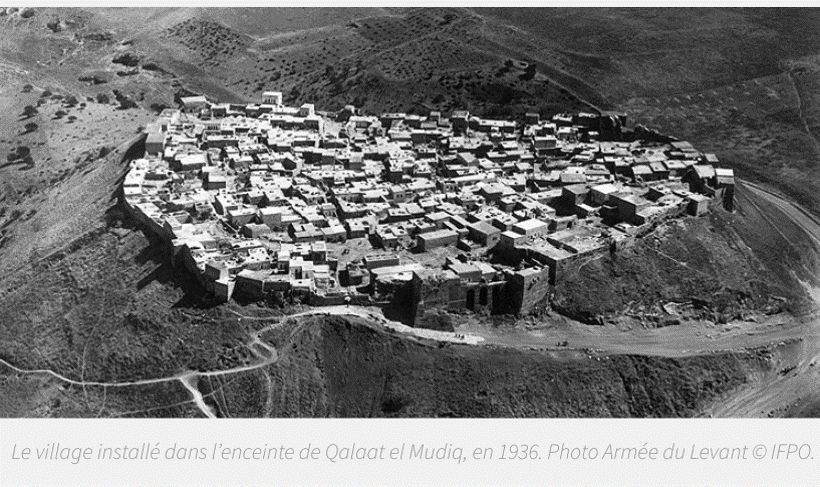

The ancient Syrian city of Apamea on Orontes (Afamia) is divided between a lower Hellenistic-Roman settlement, with its famous colonnades, and the citadel (or tel) of Qala’at Mudiq.

It is located near the cities of Hama, Homs and is due south of Aleppo. Apamea, once devastated by a series of earthquakes - a frequent occurrence in the Orontes valley - exists today as the modern town of Qala’at Mudiq and the archaeological park. The site has undergone extensive excavation and reconstruction by the Belgian authorities (Mission Archéologique Belge) for the best part of 80 years. And more recently, and in tandem, with the Syrian Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM). Apamea remains inscribed on the Tentative List of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

The genesis of Apamea is typically associated with the unified Syrian Tetrapolis (literally “four cities”) and Alexander’s general Seleucus’ (c. 312 BC (BCE)) endeavours to militarise the city. However, Persian references to CherronÔsos pre-date the Hellenistic era. The discovery of flint in the trial trenches or sondages of Qala’at Mudiq during the 1966 excavations supports a finding of at least a Neolithic settlement. This being the case, Apamea, with its Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Arab, Crusader and Ottoman history, is arguably one of the most ancient continually-inhabited cities in the world.

Apamea was annexed to Rome by the Roman general Pompey in 64 BCE. It was during the Roman and subsequent Byzantine periods that the town acquired its riches and familiar colonnaded structure with the thoroughfares of Cardo Maximus and Decumanus leading to one of the largest amphitheatres in antiquity. It was also during the Byzantine era that the city became noted for its philosophers and theologians.

The Menorah and Cross

In 381 CE, immediately after the First Council of Constantinople re-affirmed the Nicene Creed and the central question of the Trinity for the Christian faith, the Roman emperor Theodosius [347-395] issued two edicts. Both compelled a strict interpretation of the single Godhead: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, equal in part. Theodosius’ edicts went beyond doctrine. They signified the first attempt for the Byzantine Church to proscribe a muscular faith and eradicate its rivals. By decree Theodosius abandoned the time-honoured tradition of Roman tolerance and abandoned the time-honoured tradition of Roman tolerance and ushered in an era of unprecedented hatred for pagans and Jews alike. Maternus Cynegius, Theodosius’ First Minister or Praetorian Prefect of the Oriens (the East) forbade pagan sacrifice and destroyed the most revered temples of Hellenistic Egypt and Syria. Bishop Marcellus, Cynegius’ ardent follower, laid waste to all of the temples in and around Apamea on the Orontes in North West Syria. Two hundred kilometres away from Apamea in Callincum, present day Raqqa on the Euphrates, Judaism became the victim when a different bishop burned down the synagogue.

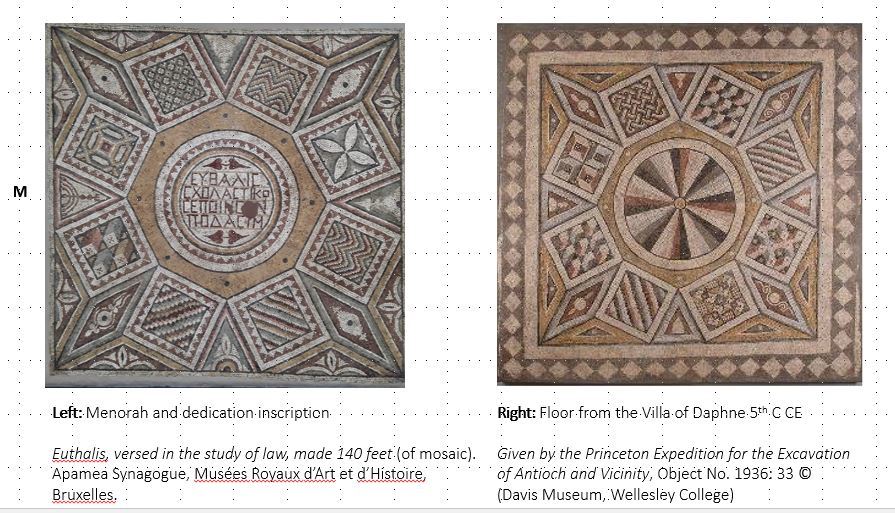

Though surrounded by acts of violence, within and beyond the city walls, the Jewish community of Apamea appeared wholly unaffected by Christian rage. In 392 CE, the Apamean Jewish elite sought sôtêria (salvation) and inscribed their pleas in tesserae. Inside the synagogue was a large mosaic floor, approximately 120 metres square, sub-divided into geometric carpets and inscribed panels. Unlike their fellow brethren at Dura Europos, the Apamean Jews adhered strictly to the Second Commandment with its prohibition against representation. Nevertheless these individuals failed to make any reference to their god whatsoever. Were it not for the smallest of seven-sided candelabra (Menorah), there would be nothing to distinguish the floor from an imperial villa save the dedicatory inscriptions.

The last days of the synagogue remains a mystery. The mosaics, now in the National Museum of Damascus as well as in Brussels, are extraordinarily well preserved. There is no sign that the mosaics were removed and recycled. All of the archaeological evidence points to the deliberate construction of the first of several churches built immediately over the synagogue floor. This had the effect of sealing it from the then world and ridding Apamea of its Jewish past.

Salvation

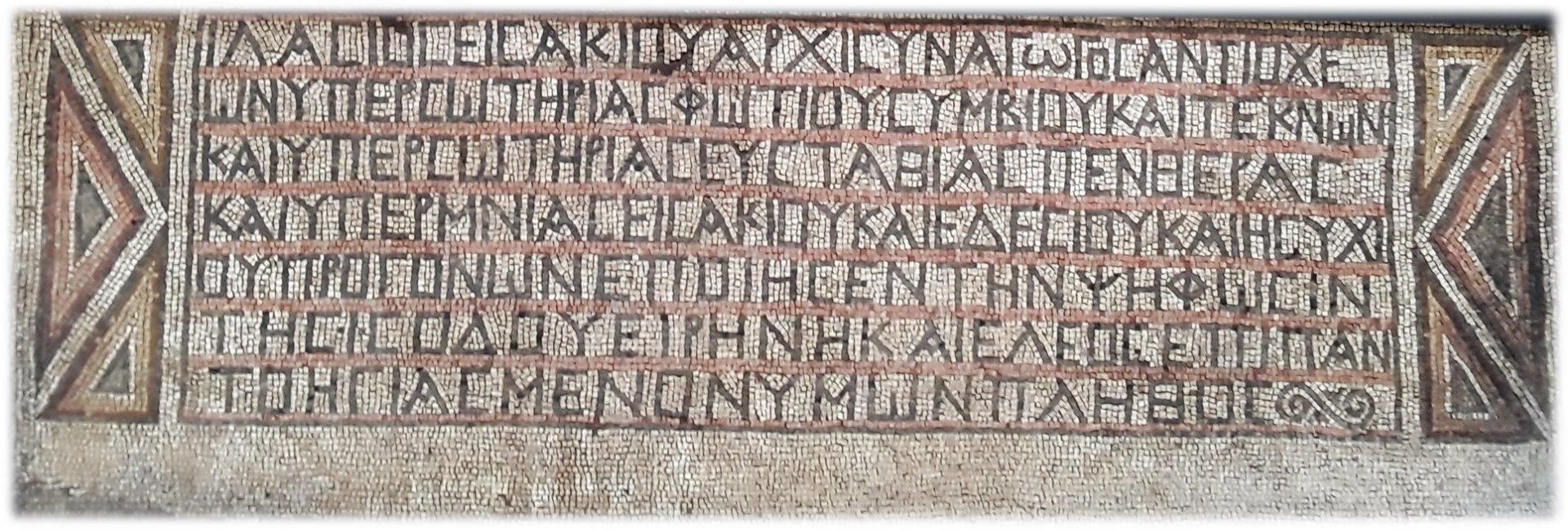

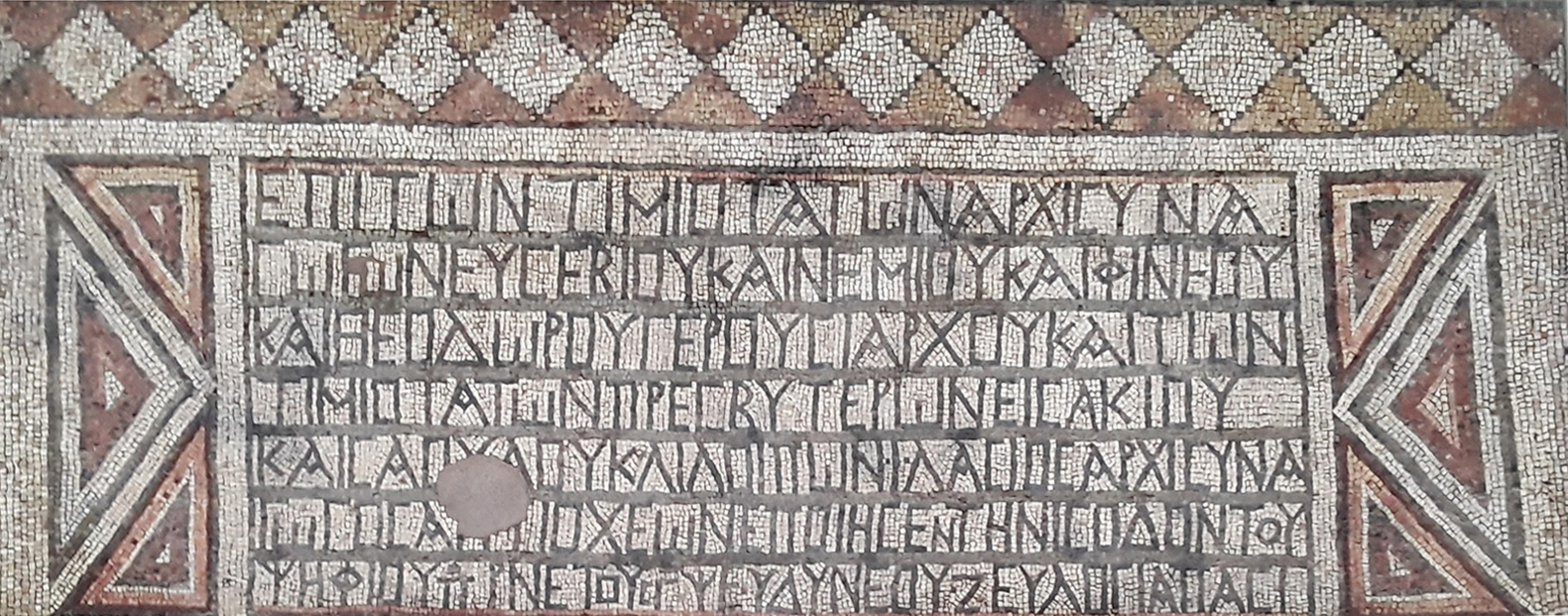

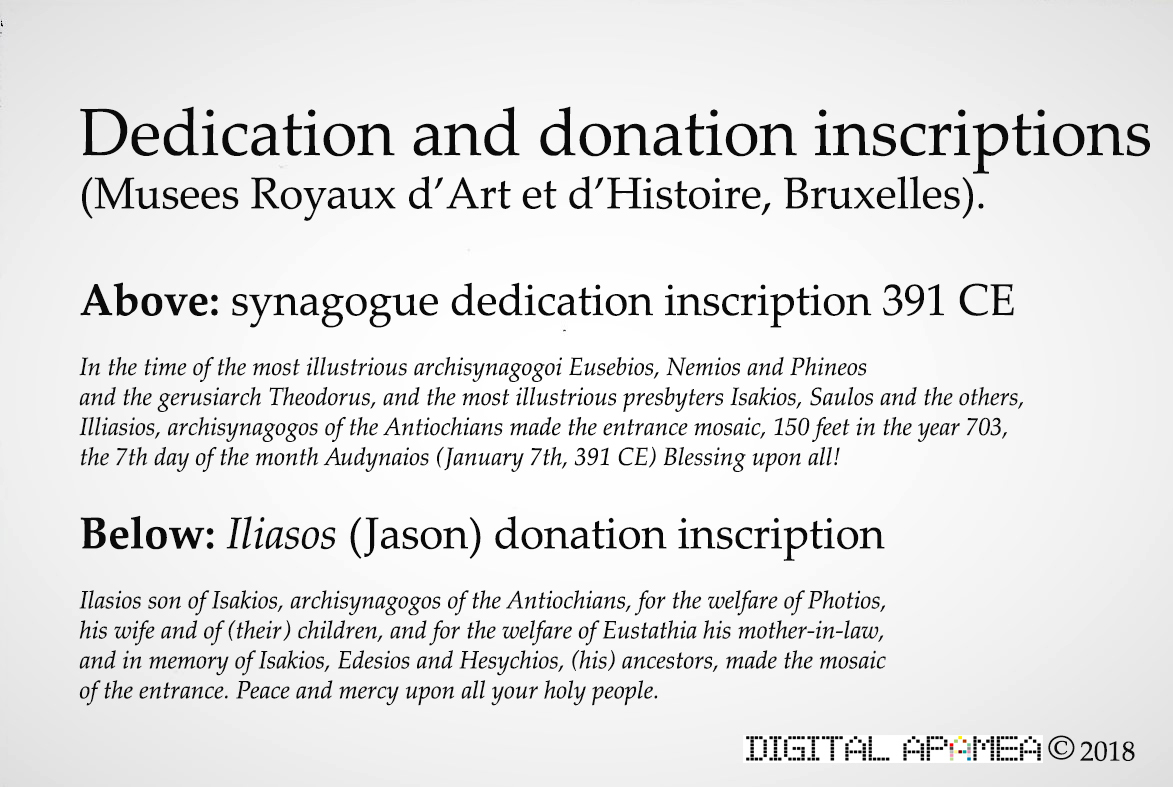

In Greek upon the newly created mosaic synagogue floor, Iiasios (Jason) the head of the synagogue or archisynagogos would declare:

“Iiasios son of Eisakos, archisynagogos of Antioch made the mosaics at the entrance for the salvation of Photion (wife) and children and for the salvation of Eustathia (mother-in-law) and in memory of Isaac and Aidesios and Hesychion (his) ancestors. Peace and mercy upon all your blessed community.”

In another inscription the same Iiasios boasts to his 4th Century congregants that he “made the entrance mosaic (for) 150 feet (in) the Year 703 Audynaios (January 7th) a blessing to all.”

The year of 703 Audynaios of the Seleucid calendar corresponds to 392 CE. The Seleucid calendar derived from the Babylonian lunisolar calendar but with substitution of Macedonian names for the Babylonian equivalent. Time began on the 1st of October 312 CE in the first regal year of Emperor Seleucus I Nicator. In the second half of the 5th Century the New Year was changed to September to coincide with the tax year.

The term archisynagogos is known from Jewish inscriptions throughout the Roman Empire. Archisynagogos is also mentioned in Tractate Yoma (a tractate of the Talmud which concerns itself with sacrificial worship of the Day of Atonement or Yom Kippur) as it the term is similarly mentioned in the Gospel of Mark (“and behold, there came one of the rulers of the synagogue, Jairus by name… Mark 5:22”). The functions of the archisynagogos were varied. They ranged from the general administration of the synagogue to supervision in the community. The role commanded much respect. And come 397 CE, 5 years later, a newly instituted law [Codex Theodosianus 16:8:13] would exempt the archisynagogos of certain state taxes and grant them a status akin to that of Christian clergy.

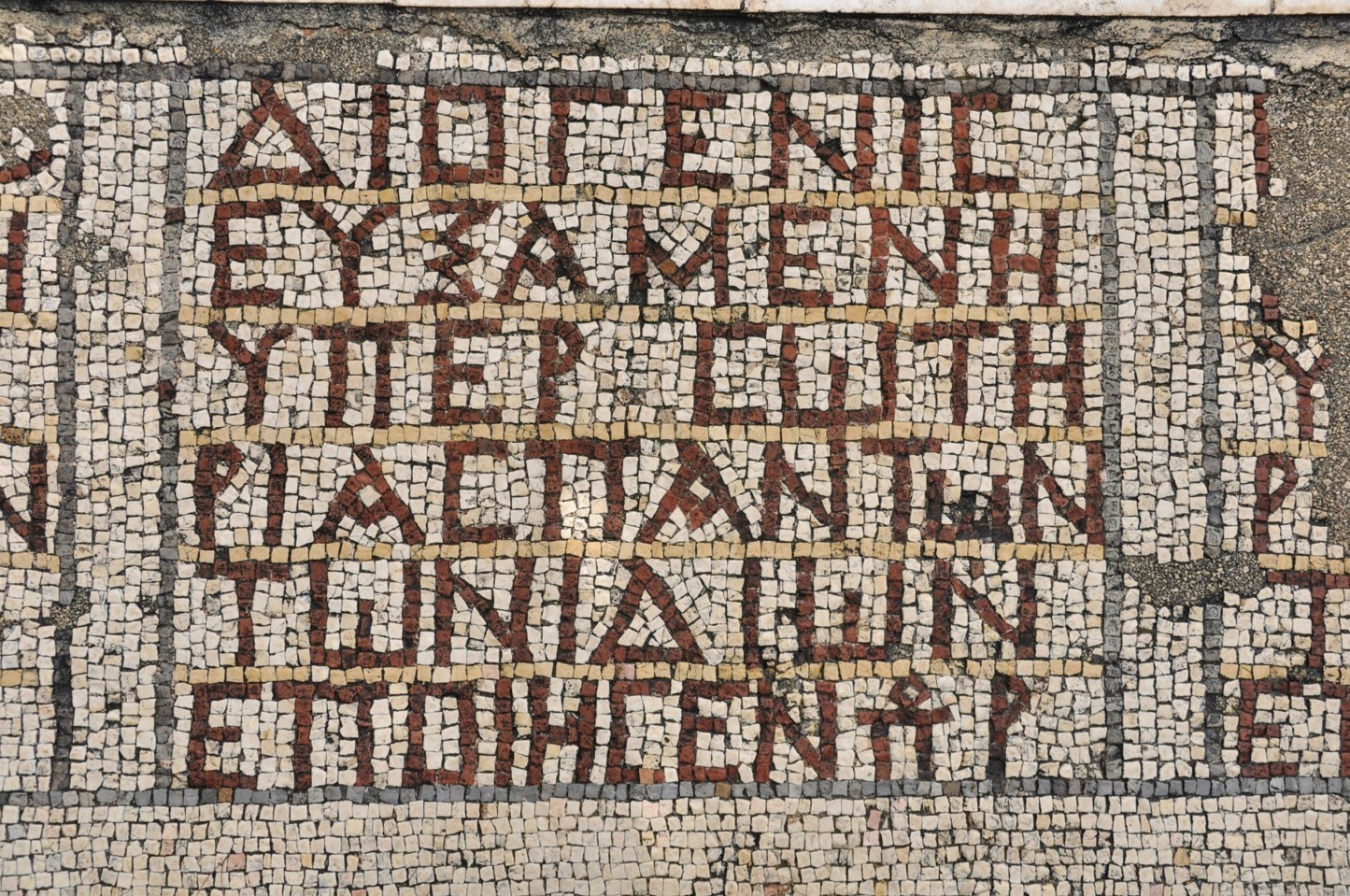

Whereas we cannot give a monetary value to the inscriptions - the cost of the mosaics per feet is unknown - Iiasios’ contribution was certainly the most generous. Nonetheless we can still see the competition at play as the patrons jostled for attention in the name of sôtêria (salvation) and with the location of inscriptions at large. Women too left their mark. They feature prominently as wives in three conjugal inscriptions as well as in the role of mother-in-law and as independent women in their own right. Nine donation inscriptions testify to this fact. Ambrosia, Domnina, Eupithis, Diogenesis and Saprika all lent their names to posterity as did Alexandria who “having made a vow made a 100 feet of mosaic for salvation of all her own.”